History has a funny way of repeating itself, especially if we do not learn from it.

In 1980, Frank Sundstrom, an American marine landed at the Kenyan coast, where he met Monicah Njeri. Njeri was what you would call a sex worker, yaani alikuwa anatafutia watoto.

One thing led to another; the two had sex, as would have been expected in such a transaction. Much later, while having drinks, Sundstrom, who claimed to have been unhappy with the ‘services’ offered, beat up Njeri, killing her in the process.

He smashed a bottle on Njeri’s head and used the broken bottle to stab her to death. He later made away with Njeri’s money.

32 years later, Agnes Wanjiru, like Njeri, met a British soldier in Nanyuki. The same thing happened and the soldier, who is yet to be identified, murdered Wanjiru and threw her body in a septic tank. Like Njeri, Wanjiru was also stabbed to death.

While Sundstrom was arrested and subjected to ‘trial’, the British soldier literally got away with murder, until about two weeks ago, when a fellow soldier decided to go public with what he knew. Britain’s Ministry of Defence thought they had successfully covered up the murder, until now.

Following an inquest in 2019, judge Njeri Thuku concluded that Wanjiru had been murdered by one or two British soldiers. The whistleblowing soldier told UK’s Sunday Times that the killer had confessed to him and he reported it but the army failed to investigate.

As for Njeri, the murder trial was presided over by a 74-year-old British expatriate judge, who released Sundstrom on a 70 dollar, two-year ‘good behaviour’ bond.

This is what the Washington Post wrote about the case then: “The verdict has brought an outcry for judicial reform from Kenyans, who point out that Sundstrom was tried by a white British judge. The white prosecutor, also British, “instead assumed the role of the defense counsel,” the daily East African Standard of Nairobi charged.”

They say why hire a lawyer when you can buy a judge.

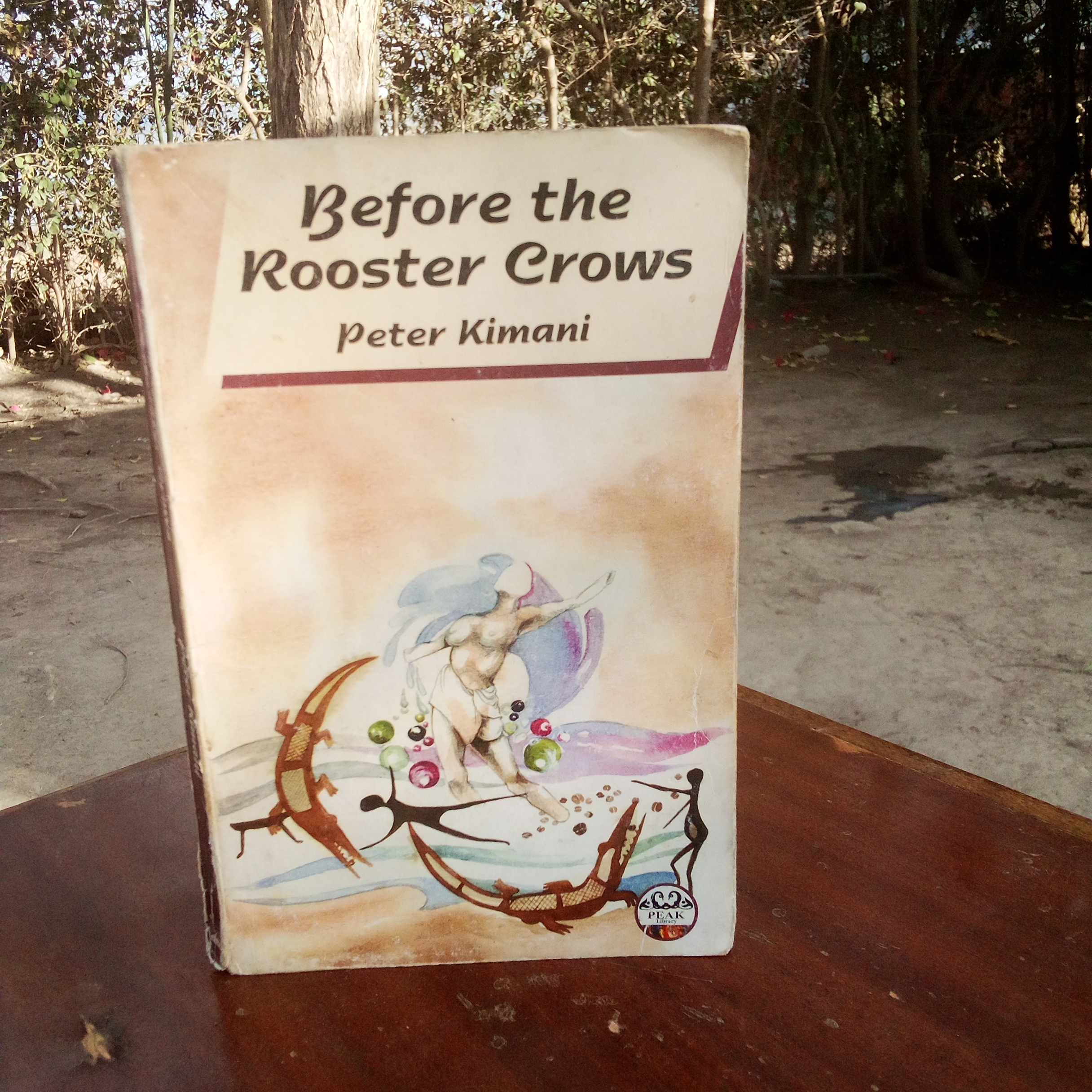

Enter Peter Kimani. In 2002, 22 years after Njeri’s murder, Kimani, then a journalist with the East African Standard, wrote his first novel, Before the Rooster Crows.

In the book, Mumbi, whose father had turned her into a wife, runs away from her village in Gichagi, to the city (Gichuka), in search of better life. To survive in the city, Mumbi turns into a flesh peddler.

Much later, she is joined by Muriuki, her village sweetheart.

Mumbi is willing to leave her old profession so the two can settle down as man and wife, but then a news item in the papers catches her attention. A ship full of American marines docks at the coast (Pwani). Mumbi convinces Muriuki to accompany her to the coast, for ‘one final job’, before finally hanging her, er, petticoat.

At the coast, Mumbi alijishindia a soldier named Desertstorm. After sex Desertstorm claims that he got a raw deal and demands his money back. A fight ensues and the marine stabs poor Mumbi with a broken bottle, a number of times, until she dies. He steals Mumbi’s money after killing her.

Muriuki happens to witness the entire episode through a keyhole, from an adjoining door, too cowardly to intervene.

Desertstorm is hauled before a British judge, who despite the overwhelming testimony against the suspect, sets him free ‘on condition that he signs a bond in the sum sh500 to be of good behaviour for a period of two years’.

Remember, Mumbi’s unlike Njeri and Wanjiru’s case, is fictional and Kimani, the author controls the narrative. Before the Rooster Crows is a historical novel and the author is out to right a historical injustice committed in 1980.

How does he do it? Stay with me…

Following the injustice occasioned on his girlfriend, through the courts, Muriuki tracks down Mumbi’s killer and strangles him to death.

Cue another trial, this time with Muriuki on the dock. Meanwhile, there is huge outcry and judge – the same one who freed Desertstorm – recuses himself from the case. It becomes clear that justice might finally be done, or would it?

In the intervening period, a bill is brought before parliament to the effect that the president can intervene in an ongoing case and deliver judgement. That is precisely what was done and Muriuki was sentenced to death.

This was obviously a case of foreign interference, just like in Njeri’s case, to arrive at crooked justice.

However, in the realm of fiction, the author has is in charge and that is how he ensured that Mumbi gets some justice, no matter how rough.

Now, since we did not learn from the 1980 murder, that is why history had to repeat itself with the Nanyuki murder.

This book is a must read for anyone interested in good writing. I wonder why the fellows at the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) have to engage in the charade of looking for setbooks, when such a gem gathers dust on bookshelves.

Kimani’s publishers, EAEP, should tell readers if the book is still in circulation.

Kimani is also the author of Dance of the Jakaranda, another historical novel, which is doing well internationally.