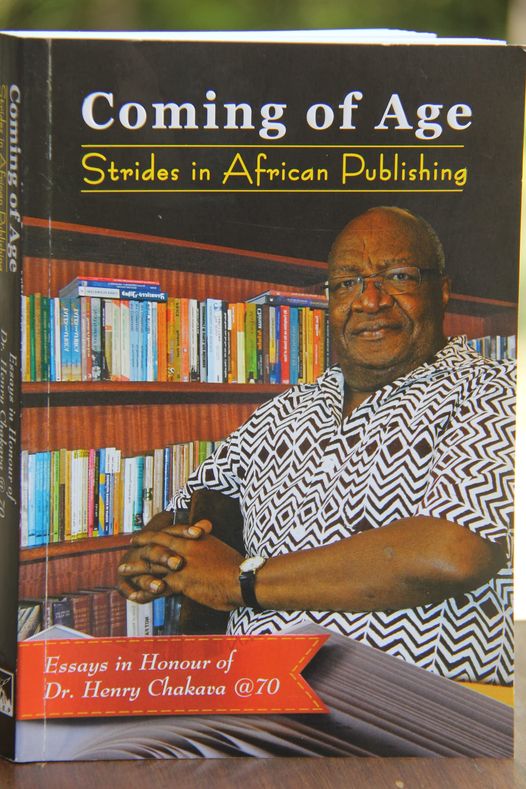

Henry Chakava, has been referred to as the father of African publishing for good reason.

He would have easily made a career in the academy but he chose publishing instead. In 1972, he joined the then Heinemann Educational Publishers as an editor. In a span of six years, he had risen to the position of managing director.

In the early nineties he bought the company from its UK owners and named it East African Educational Publishers. However, the most enduring part of his story is how he led his company to publish more than 2,000 tiles of culturally relevant books – which include fiction – the largest by a local publishing house.

He managed this by balancing between publishing school publishing – the bread and butter of local publishing – and publishing for leisure/fiction.

Despite the fact that his employers, Heinemann, were the publishers of the successful African Writers Series, he kept receiving manuscripts which he felt would fit into a new genre of adventure, romance and crime.

He floated the idea to his bosses in the UK but they flatly rejected the idea. He would not take no for an answer and went ahead to start the Spear Series, which became so successful, that Heinemann had to start a series of their own called Heartbeat.

Chakava received the manuscript of My Life in Crime from Kamiti Maximum Prison, where the author, John Kiriamiti, had been imprisoned for robbery with violence. To date, My Life in Crime remains Kenya’s best-selling novel.

It should be remembered that Chakava is also Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s publisher. For Chakava, publishing Ngugi was a challenge, a risk and reward. Challenge in the sense that as a committed writer, he expects the publisher to share his vision. And for that he has given Chakava all the due respect.

Another challenge had to do with distribution of his works following Heinemann’s take over by East African Educational Publishers. Without the network of distributing the works abroad, Chakava had the daunting task of distributing them.

The risk came from the fact that Ngugi, in the 70s, was deemed as anti-government, controversial and a rebel. And that came with a stigma. And isolation. And the reward came because Ngugi’s books were intellectually and commercially rewarding as a recognised name.

When, in 1980 word spread that Chakava was about to publish Ngugi’s book, Caitani Mutharabaini, (Devil on the Cross) written in detention, he started receiving threatening phone calls. When the aggrieved parties – suspected to be government agents – saw that he was unrelenting, they decided to move their dastardly action to the next level; assassination. Chakava was waylaid as he was about to enter his Lavington home, by thugs armed with all manner of crude weapons. He was only saved by headlights of an oncoming vehicle. The thugs dispersed but not before a machete, aimed at his head, almost severed his small finger.