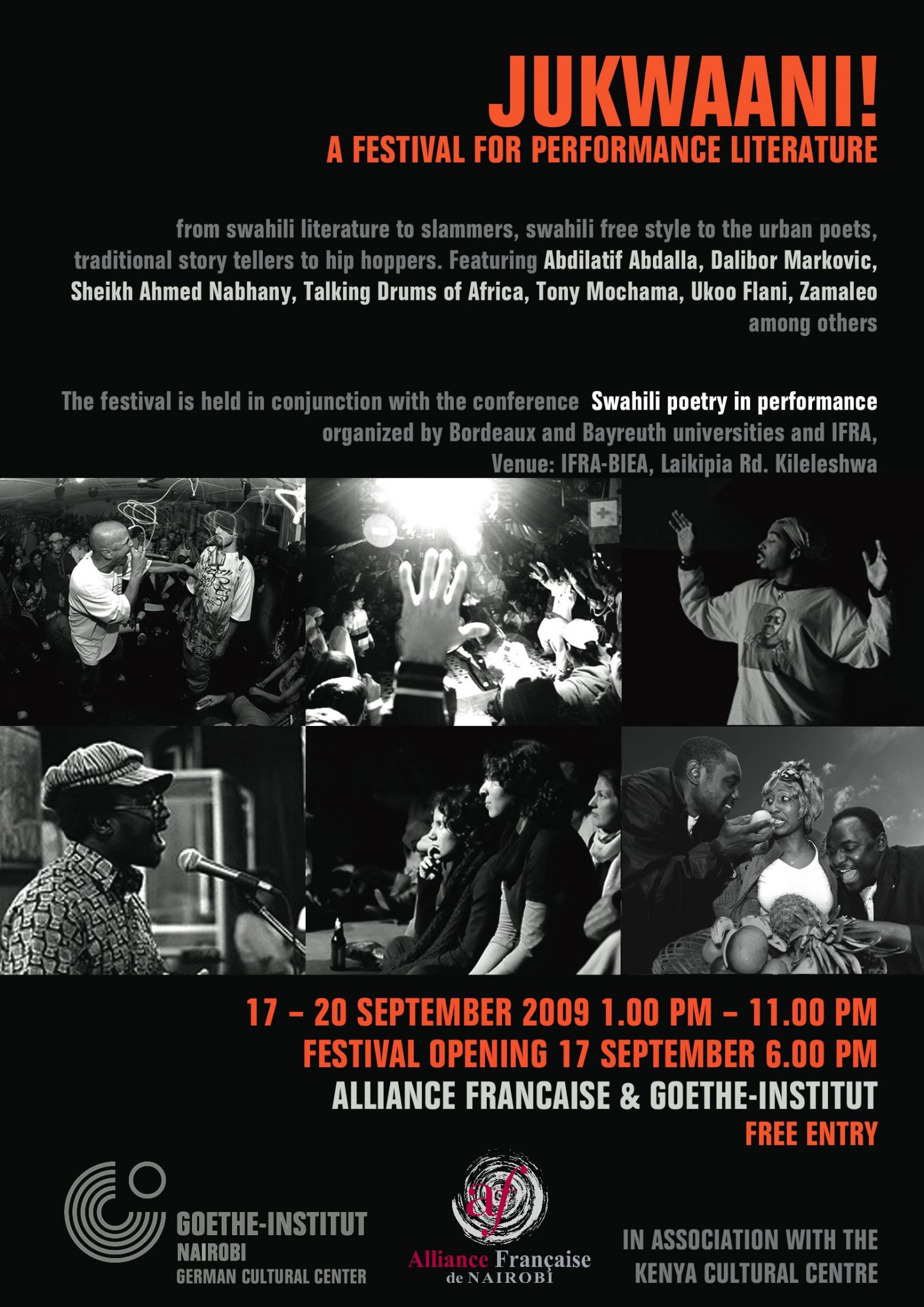

African culture has from time immemorial been transmitted, from one generation to the other, through the spoken word. This goes to show why the fireside stories, often told by grandmothers, occupy such a central place in the African literary setting. The study of African literature is not complete without talking about oral literature. Some of the greatest African novelists trace the roots of their prowess from the stories they were told by their grandmothers when they were growing up. Here, Chinua Achebe of the Things Fall Apart fame comes to mind. Performance literature has, over time, undergone a transformation in tune with modern trends. Still, this form of art is highly cherished in Africa. Perhaps the finest form of performance literature are poetry recitals which come in various forms, ranging from poetry slam to spoken word. In a move to celebrate performance literature, the Kenya Cultural Centre, the Goethe Institut and Alliance Francaise will be holding a one-of-its-kind festival from 17 to 20 September, whose entry will be free.

Dubbed Jukwaani! the festival will feature a blend of the new and old as far as East African performance literature is concerned. The five-day event will also feature European-based African artistes as well as those from Europe. The performances will mostly be in English and Kiswahili. Among the personalities set to perform during the festival is German-based poet and scholar Abdilatif Abdalla. Most young Kenyan’s would not be immediately aware of Abdilatif nor his achievements. In literary circles, he is best known for his protest works. The Kenyatta regime jailed him after he wrote the book Kenya Twendapi? (Kenya; where are we headed?) This book criticised the Kenyatta government for its excesses and neo-colonial stance. He was actually charged with sedition. His other book, Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony), a collection of poetry was written while he was incarcerated at Kamiti Maximum Prison. It was basically agitating for the opening up of democratic space in Kenya. Sauti ya Dhiki went on to win the inaugural edition of the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature in 1974 for the Kiswahili category. Ukoo Flani Mau Mau, better known for their lyrical prowess, will also be part of Jukwaani! attractions. Ukoo Flani, draw their inspiration and creativity from the day-to-day struggles in Nairobi slums. They are based in slums of Dandora. Best known as underground artistes, these Dandora-based hip-hoppers have chosen to remain true to their impoverished slum existence by shunning the more commercial forms of creativity. Theirs is the hard-hitting poetry that depicts typical life in the slums, their suffering, in the hands on corrupt authorities, as well as triumphs. They also document the negative side of life in the slum, like the effects of crime and drug abuse. Ukoo Flani are a direct contrast to the other form Kenya’s urban hip hop, which appears to celebrate materialism, commonly expressed in the form of flashy lifestyles and bling. Proceeds of their album Kilio cha Haki are going towards the creation of a permanent studio in Eastlands. This, they argue, will help to give young Kenyans a voice and demonstrates how hip hop and music can be an alternative to drugs and crime; a source of income; a means of voicing social and political protest. Truth be said Ukoo Flani boasts some of the finest urban poets in Kenya today, and it is their lyrical prowess that will be showcased at the festival. Tony Mochama, also known as the Literary Gangster, for his unconventional and often abrasive poetry, will also be performing at Jukwaani! The moniker Literary Gangster was inspired by the title of his book, What if I am a Literary Gangster, a collection of poetry. Other featured performers include Dalibor Markovic, Sheikh Ahmed Nabhany, Talking Drums of Africa, and Zamaleo, among others. While the example of Abdilatiff Abdalla goes to show that performance literature has been in existence for a long time, particularly among the Swahili people, the idea of performance poetry has caught up among urban youth in the last four years. Perhaps the best known is Open Mic poetry sessions organised on a monthly basis by Kwani Trust. The idea of Open Mic is borrowed from the American inspired Poetry Slam. Here a number of poets take to the stage to perform their poems and are awarded points from either a panel of judges or the audience. Spoken word is the other form of performance poetry, which is often accompanied with a musical background. Compared with Southern African countries, East Africans lag behind when it comes to performance poetry. Zimbabwe for example, has a well-established poetry movement, which has been at the forefront in the agitation for opening up of democratic space in the country. Jukwaani! as the name suggests, will mainly centre on what is on show on the podium. Jukwaani is Kiswahili for on the stage or podium. Jukwaani! hopes that the boundaries separating the performer from the audience will be shattered leading to a situation where the audience is fully involved.