Sometime back I compiled a list of what I thought we the top ten Kenyan books of all time. I actually did the project to coincide with Kenya’s Jubilee celebrations. Since this list is mine some of my readers might feel that it is not complete or even subjective, but hey one has to start somewhere. What are your thoughts?

- The River Between

This is the book that introduced Ngugi wa Thiong’o as a writer of note. Following in the tradition of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, The River Between tackled the issue of the clash between African traditions and customs, on the one hand, and the white man’s way of life and religion (Christianity) on the other. This book has been the subject of heated debate among readers as to the real message Ngugi wanted to convey, despite the fact that it has been a school set book more than once. At some point a critic took an extreme view and accused Ngugi of being a Mungiki sympathiser, probably due to his elucidation of Gikuyu culture in this book.

- Going Down River Road

Meja Mwangi has been hailed as Kenya’s foremost urban writer. While his more decorated colleague Ngugi wa Thiong’o based his writing in a rural setting, Meja Mwangi scoured the African urban districts for inspiration. Going Down River Road, alongside his other two urban-based books Kill me Quick and Cockroach Dance form some of his most inspired writing to date. With memorable characters like, Ben, Ochola, Baby and Yusuf, Meja Mwangi introduced a certain romance to Nairobi’s River Road. Is any wonder then that critics have compared the squalor and hopelessness in this book to Gorky’s Russia. There are Kenyan readers who swear that Ngugi cannot hold a candle for Meja Mwangi when it comes to writing.

- After 4.30

The Kenyan literary menu cannot be complete without David Maillu’s After 4.30 among his other offerings of Kenya’s version of erotica, like My Dear Bottle. Many Kenyans above the age of 40 will confess to secretly – mostly in class – absorbing Maillu’s titillating details from well-thumbed copies of After 4.30, in their hormone-driven teenage years. There were also the holier-than-thou types who loudly castigated After 4.30, and those who read it, in public, but were themselves devouring it in the secrecy of their bedrooms. Those who condemned After 4.30 and Maillu’s other bawdy writings should ask themselves why Fifty Shades of Grey has become such a global hit.

- Betrayal in the City

This is the one play that put the late Francis Imbuga on the literary map. Betrayal in the City that recently made its way back as a school set book, was written in the 1970s and the issues it addresses are still as relevant today as they were then; corruption and abuse of power in government and impunity by leaders and their sycophants. To get services in government offices, according to Betrayal in the City, one needs a ‘taller relative’, more like the modern, ‘you should know people’. It is this book that introduced lexicon like ‘green grass in snake’ – a corruption of green snake in grass – and ‘I wonder why you possession that thing between your legs’.

- Across the Bridge

“Hail jail! the place for all …” or so goes the beginning of the recently departed Mwangi Gicheru’s Across the Bridge. It tells the story of Chuma who, it today’s lingo, would be called a hustler, who achieves the unprecedented feat of impregnating Caroline the daughter of rich man Kahuthu. The adventure that follows there after that is one that will either leave you in tears or with cracked ribs. Any book lover, of over 35 years, and who hasn’t read this book should bow their heads in shame and never utter a word in the company of serious book lovers. This book was Kenya’s version of James Hadley Chase; it was that good.

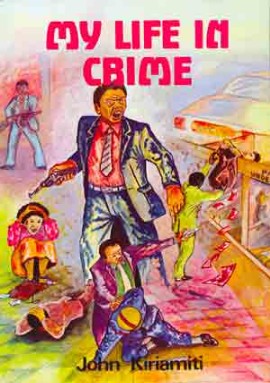

- My Life in Crime

My Life in Crime by John Kiriamiti is by Kenyan standards a best-seller. Yes this is a book which, despite never having been a school set book continues to fly off the shelves. John Kiriamiti a reformed bank robber wrote this book while serving time at Kamiti Maximum Prison. Ngugi wa Thiong’o is among the people that recommended the manuscript be published. This crime thriller, a fictionalised account of Kiriamiti’s life as a criminal, captured the imaginations of young Kenyans who read it. There had been talk of it being turned into a movie, but the initial excitement has since fizzled down.

- The River and the Source

The River and the Source by the late Dr Margaret Ogola burst into the scene when it won the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, in 1995. It went on to win the prestigious Commonwealth Writer’s Prize, for Africa, that same year. Shortly after it became a school set book. Those who studied the book in high school have nothing but praise for this book that celebrates the place of the woman and the girl child in African societies. The author, a pediatrician, outdid herself in celebrating Luo culture. For its strong women characters, this book has been hailed as Kenyan’s manual for feminists.

- The Last Villains of Molo

Kinyanjui Kombani, a banker, to date remains the only Kenyan writer to have comprehensively tackled the subject of Kenya’s tribal/ethnic clashes. Ethnic violence, as we know it, has recurred in Kenya’s Rift Valley every election circle since 1992 – apart from 2002 – and degenerated into the killing fields that greeted the disputed 2007 presidential election. The Last Villains of Molo enters this list for its sheer audacity to confront the demons of ethnic violence at a time when mentioning tribes, in any form of writing, was frowned upon. Kombani goes ahead and prescribes reconciliation as the surest way of ending such hostilities. It is instructive to note that the author grew up and went to school in Molo, which for the longest time, was the epicentre of this politically instigated violence.

- From Charcoal to Gold

The late Njenga Karume’s autobiography From Charcoal to Gold is probably the very first of such genre to have captured the psyche of Kenyans. For a long time Kenyans had been fascinated by the former Defence minister’s rags-to-riches story, in spite of the fact that he received little or no formal education. It was therefore quite something when the man himself put his story in writing thereby clearing out some myths and misconceptions. Readers got to know how Njenga shrewdly negotiated his way through the complex world of business from a humble charcoal-seller to becoming one of the richest men in Kenya and who would later become a confidant and much sought-after power-broker in Kenya’s first three governments. The book has also become a must-have motivational book.

10. Peeling back the Mask

If there is a book that shook the foundations of Kenya’s political life, then Miguna Miguna’s book Peeling back the Mask is it. Miguna says the book is his autobiography but many Kenyans will remember it for the unflattering take at former Prime Minister Raila Odinga. Muguna was after all Odinga’s close confidant and political advisor. It was after the two fell out that the former decided to publish the book. For months, this book sparked heated political debate with supporters and detractors of the former Langata MP taking opposite sides. Peeling back the Mask also takes the cake for sheer nuisance value. There are those who hold the view that this book dealt a mortal blow to Odinga’s chances of ascending to the presidency in the March 2013 elections.